By Jessica Rosen, Curatorial Assistant

This collection spotlight is the second in a series that highlights the voice of the important art critic and art historian Elizabeth McCausland (American, 1899–1965), whose career plays a central role in the exhibition Embracing the Parallax: Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland. While McCausland was one of the most forward-thinking critics of her time, today her name has been all but forgotten. McCausland’s correspondence with and writing about artists whose work is in the collection of The Heckscher Museum demonstrates her significant role in the twentieth-century art world and beyond. Embracing the Parallax celebrates the prolific collaboration between McCausland and her romantic and intellectual partner, photographer Berenice Abbott (American, 1898–1991), with a focus on their celebrated photobook, Changing New York (1939).

This collection spotlight is the second in a series that highlights the voice of the important art critic and art historian Elizabeth McCausland (American, 1899–1965), whose career plays a central role in the exhibition Embracing the Parallax: Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland. While McCausland was one of the most forward-thinking critics of her time, today her name has been all but forgotten. McCausland’s correspondence with and writing about artists whose work is in the collection of The Heckscher Museum demonstrates her significant role in the twentieth-century art world and beyond. Embracing the Parallax celebrates the prolific collaboration between McCausland and her romantic and intellectual partner, photographer Berenice Abbott (American, 1898–1991), with a focus on their celebrated photobook, Changing New York (1939).

Elizabeth McCausland championed American modernist Alfred H. Maurer (1868–1932), highlighting the ways that his life and career expanded the boundaries of American art. She wrote the first in-depth biography on Maurer and curated his first major retrospective exhibition. She conducted extensive primary research on his life and work, an effort that has proved invaluable to future historians. McCausland highlighted an artist who was overlooked in his lifetime and her writing increased the visibility of his wide-ranging career. In the following article, I examine the ways McCausland’s advocacy for Maurer made an indelible impact on the art world.

Elizabeth McCausland championed American modernist Alfred H. Maurer (1868–1932), highlighting the ways that his life and career expanded the boundaries of American art. She wrote the first in-depth biography on Maurer and curated his first major retrospective exhibition. She conducted extensive primary research on his life and work, an effort that has proved invaluable to future historians. McCausland highlighted an artist who was overlooked in his lifetime and her writing increased the visibility of his wide-ranging career. In the following article, I examine the ways McCausland’s advocacy for Maurer made an indelible impact on the art world.

Maurer’s artwork was incredibly varied, demonstrating his willingness to take risks, change, and evolve. He was trained in academic painting, but, after being exposed to modernism in Paris, his style shifted: he rejected realism in favor of a lifelong commitment to abstraction. In 1932, aged 64, Maurer died by suicide.

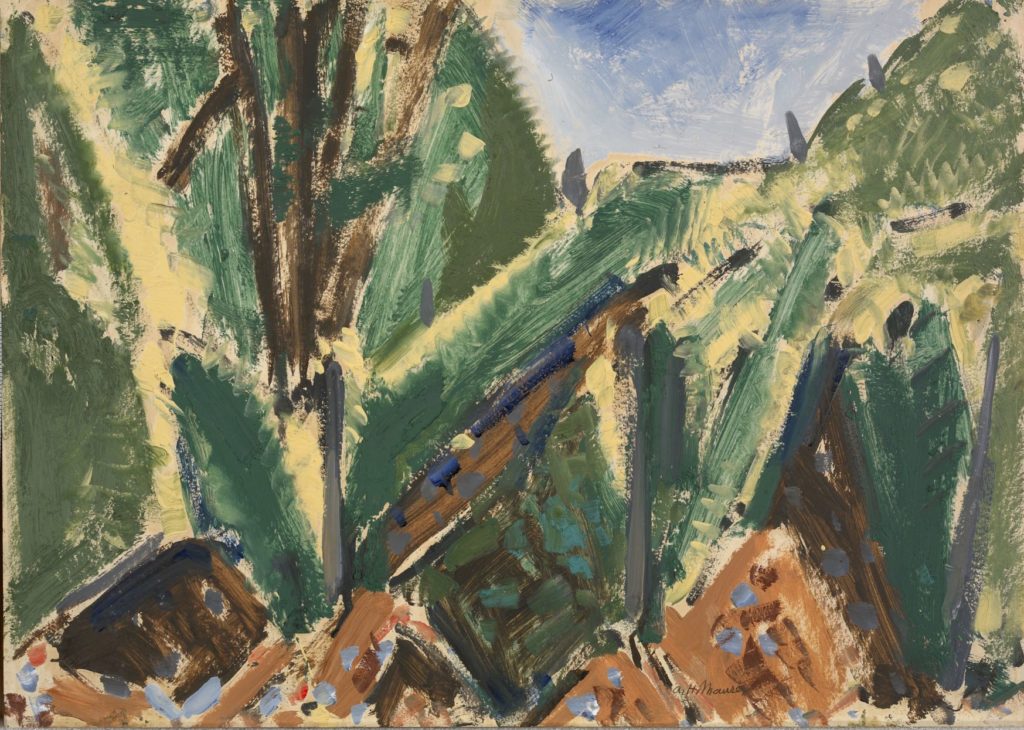

McCausland wrote that Maurer “looked to nature and to life for his sources.” This is true of the three works by the artist in the Heckscher Museum’s collection. Landscape (n.d.), Flowers on a Yellow Table (1926), and Female Nude (c. 1927–28) represent subjects that Maurer came back to throughout his career as he experimented with new ways to represent landscapes, still lifes, and figures.

In 1933, McCausland first learned of Maurer’s art through her friendship with modernists Arthur Dove and Helen Torr (see Collection Spotlight: McCausland and Dove). In an article published in The Springfield Republican in 1937, she astutely wrote, “Maurer is a real American of his generation, a sensitive, poetic nature, open to wounds. . . . his abstractions are intellectual experiments, they seem more like the armor he forged against the world’s blows.”

By 1948, sixteen years after Maurer’s death, McCausland was leading the research for an exhibition and book supported by The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. She established a Maurer archive by conducting interviews with his family and close friends, gathering his correspondence, and compiling mentions of him in art world publications. Further, McCausland undertook the task of dating thousands of Maurer’s works. On June 5, 1948, McCausland wrote to Maurer’s sister, Eugenia Maurer Fuerstenberg, “we have photographed about a thousand oils, gouaches, and watercolors.” She cross-referenced these photographs with her research notes to date his work. You can get a glimpse of her system here.

All of McCausland’s hard work culminated in a traveling exhibition in 1949, and a biography published two years later. A. H. Maurer: 1868–1932, curated by McCausland, was presented at The Walker, the Whitney, and six other venues. Her book A. H. Maurer (1951) received critical acclaim. One review by curator and museum director Holger Cahill exclaimed that McCausland “has written of Alfred H. Maurer not only with warmth and sympathy but with passionate conviction . . . . Her respect for her subject and for the reader is evident in everything that she does, in her careful and thorough research, in her positive approach, and in a willingness to go out-on-a-limb if need be to create the metaphor which gives the story dramatic presence. Alfred Maurer, the man and artist, comes alive in her book. He is here. This is an important contribution to the literature of modern art in America.”

All of McCausland’s hard work culminated in a traveling exhibition in 1949, and a biography published two years later. A. H. Maurer: 1868–1932, curated by McCausland, was presented at The Walker, the Whitney, and six other venues. Her book A. H. Maurer (1951) received critical acclaim. One review by curator and museum director Holger Cahill exclaimed that McCausland “has written of Alfred H. Maurer not only with warmth and sympathy but with passionate conviction . . . . Her respect for her subject and for the reader is evident in everything that she does, in her careful and thorough research, in her positive approach, and in a willingness to go out-on-a-limb if need be to create the metaphor which gives the story dramatic presence. Alfred Maurer, the man and artist, comes alive in her book. He is here. This is an important contribution to the literature of modern art in America.”

McCausland ended her book with an epitaph “written by one who loved him,” namely, his closest friend, Dove, who wrote, “I think we knew each other better than anyone . . . . No death has ever hurt so much when life was so beautiful and had such possibilities leaving out the career-conscious side of it.” Dove and Maurer were so close that “after Maurer’s death, his walnut bed and wood carving tools came to rest with Dove in the old farmhouse outside Geneva, in the Dove Block skating rink, and finally in the former post office at Centerport to which Dove and Helen Torr Dove moved from upper New York state.”

McCausland’s comprehensive biography and traveling exhibition solidified Maurer’s place in the art world. Today, he is recognized as an artist who was ahead of his time, paving the path for future American modernists. Without McCausland’s diligent research and advocacy for his art and his story, we would not remember him as the creative force that he was. McCausland wrote, “Maurer sought to understand the meaning of life . . . . At the end, he found his answer only in endurance. To that degree he transcends his private language and speaks for all who suffer yet endure.”

To read more about McCausland’s research on Maurer, which has been digitized by the Archives of American Art, click here. You can read McCausland’s A. H. Maurer for free with an Internet Archive account, here.

Embracing the Parallax: Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland is sponsored by Susan Van Scoy, Ph.D., Brian Katz & Olshan Frome Wolosky LLP. This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.